Probiotics: New Frontiers in Immune Modulation

Probiotics are nonpathogenic strains of bacteria that live in the human body and perform functions associated with health benefits.[1] An increasing area of focus in probiotic research is the impact of probiotics on immune function. Probiotics have been shown to both improve resistance to infection as well as promote the induction of tolerance. In this way, they are like adaptogens for the immune system: They can both boost the immune response if impaired, but they can also dampen the autoimmune response. This bimodal action, combined with a high safety profile, lends probiotics a high level of utility for a variety of illnesses and health concerns.

Beneficial bacteria have been shown to interact with immune cells on a molecular level. Polysaccharides expressed on the surfaces of Lactobacillus strains, for instance, have been shown to bind specific receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) and lectin receptors present on immune cells such as dendritic cells and T lymphocytes, and influencing their production of immune-active chemicals called cytokines.[2] Depending on what family of cytokines is produced, this may result in a pro- or anti-inflammatory response, thereby exerting an immunoregulatory effect.[3][4] According to Kang: “Depending on types of probiotic species, they can either induce immune activation signaling by producing IL-12, IL-1β, and TNF-α, or trigger tolerance signaling by stimulating anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β levels.”[1] Probiotics may also secrete anti-inflammatory molecules independently.

In humans, probiotics have been shown to reduce upper respiratory tract infections (URTI); reduce gastrointestinal infections including Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (ADD), and traveller’s diarrhoea; reduce vaginal infections (yeast or bacterial); and maybe reduce bladder or urinary tract infections. Supplementation with probiotics also appears to modulate the autoimmune response in conditions including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), asthma and eczema, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Respiratory Infection

Human studies show that supplementation with probiotics has been shown to reduce the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) among adults, children, athletes, and the elderly.[5][6][7] High probiotic doses have been shown to significantly increase the percentages of activated potentially T-suppressor and NK cells, while low probiotic doses increased activated T-helper lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and antigen-presenting cells.[5]

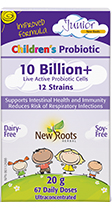

In children, probiotic supplementation was shown to result in a 25% decreased risk of having an episode of respiratory or gastrointestinal illness during the winter.[6] In children with asthma, supplementation with a symbiotic containing 1 billion CFU significantly reduced the risk of viral illness and reduced the use of salbutamol inhaler medication.[8] A 2016 meta-analysis of 23 studies found that probiotic supplementation decreased the number of children (newborn to 18 years old) having at least one respiratory tract infection, and decreased the numbers of days absent from daycare/school.[9]

Gastrointestinal Infection

In addition to the mechanisms described above, probiotics exert a competitive regulatory effect on other microorganisms in their local environments. For instance, in the gastrointestinal tract, bacterial and yeast species are in constant competition for nutrients as well as binding space in the gut, inhibiting the overgrowth of harmful species.

Treatment with antibiotics alters the balance of bacteria of the gastrointestinal system, and may cause antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD).

“A 2012 meta-analysis of 82 clinical trials found that probiotics reduce the risk of AAD by up to 42%.”[10]

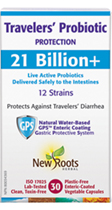

Another infectious diarrhoea, traveller’s diarrhoea, often includes infection with Escherichia coli (E. coli). A Cochrane meta-analysis found that probiotics are an effective treatment for infectious diarrhoea, reducing the duration of symptoms by over 24 h, and reducing the risk of diarrhoea persisting for more than four days by almost 60%.[11]

Finally, H. pylori is a common gastrointestinal infection and bacteria associated with peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori is typically treated with a combination of antibiotics and antacids called “triple therapy,” which is associated with an eradication rate of about 70–80%. The addition of probiotics to this regimen can increase the eradication rate up to 96%.[12]

Vaginal/Bladder Infection

The vaginal microbiota also functions as an inhibitor of yeast overgrowth, which may happen in association with antibiotic treatment or with hormonal fluctuations associated with the menstrual cycle and/or menopause. Oral and vaginal suppository use of probiotics has been shown to help prevent recurrent vaginal yeast infections as well as cystitis or bladder infections.[13][14]

Autoimmune Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Autoimmune disease is characterized by an overactive immune response, such that the immune system mounts an attack on the body’s own tissues and organs.

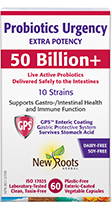

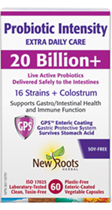

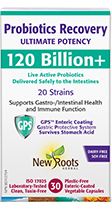

Inflammatory bowel disease is an autoimmune disease of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). Probiotics have been shown to help maintain remission of ulcerative colitis, when used in more general doses such as 20 billion CFU, up to doses between 50 and 900 billion CFU per day.[15] Probiotics have also been shown to reduce symptom severity during active disease, induce remission in some patients, as well as prolong periods of disease remission in patients with IBD.[16][17][18][19] Trials utilizing 50–200 billion CFU have shown a reduction in symptoms and histological score (a measure of tissue damage) in patients with Crohn’s disease.[16][20]

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a highly inflammatory condition affecting the small joints of the hands as well as other joints throughout the body. It is associated with progressive joint damage and loss of function. Probiotics have also been shown to reduce disease activity and inflammation in patients with RA. For instance, among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, supplementation with probiotics for eight weeks was found to significantly reduce the disease activity score of 28 joints (DAS-28); reduce C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation; and improve insulin resistance compared to placebo.[21] Another study found that supplementation with probiotics resulted in decreased serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels and decreased tender and swollen joint counts, and improved global health (GH) score and DAS-28, compared to placebo.[22]

Atopy: Eczema, Asthma, and Allergy

Finally, probiotics have been shown to improve atopic disease including asthma, eczema, and allergy. Supplementation with Lactobacillus strains in children with asthma has been shown to decrease bronchial inflammation,[23] improve pulmonary function, and decrease symptom scores for asthma and allergic rhinitis compared to placebo.[24] There was also a significant reduction in cytokines, specifically TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-13, production following probiotic treatment.[24]

Importantly, when taken during pregnancy, probiotics appear to modulate the development of the fetal immune system. This is made evident by the fact that the offspring of women supplementing with probiotics have a decreased risk of developing atopy. A recent meta-analysis examined 17 studies, including 4755 children, and found that supplementation with probiotics during pregnancy and early infancy was associated with a 22% lower risk of eczema compared to untreated infants, and this was especially marked in children who received a mixture of probiotics.[25] These children had an almost 50% reduced risk. Another meta-analysis found that probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and early infancy may reduce the risk of atopy as well as food hypersensitivity in the infants.[26]

In conclusion, probiotic bacteria may well be the new immune adaptogen, anti-infective, and immune regulator wrapped up into one. Research in this area continues to unravel new roles for probiotics in immune modulation and the benefits of supplementation on specific conditions.

References

- Kang, H.J., and S.H. Im. “Probiotics as an immune modulator.” Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. Vol. 61 Suppl. (2015): S103–S105.

- de Kivit, S., et al. “Regulation of intestinal immune responses through TLR activation: Implications for pro- and prebiotics.” Frontiers in Immunology. Vol. 5 (2014): 60.

- Bene, K.P., et al. “Lactobacillus reuteri surface mucus adhesins upregulate inflammatory responses through interactions with innate C-type lectin receptors.” Frontiers in Microbiology. Vol. 8 (2017): 321.

- Balzaretti, S., et al. “A novel rhamnose-rich hetero-exopolysaccharide isolated from Lactobacillus paracasei DG activates THP-1 human monocytic cells.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Vol. 83, No. 3 (2017): e02702–e02716.

- Mañé, J., et al. “A mixture of Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7315 and CECT 7316 enhances systemic immunity in elderly subjects. A dose-response, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized pilot trial.” Nutrición Hospitalaria. Vol. 26, No. 1 (2011): 228–235.

- Cazzola, M., et al. “Efficacy of a synbiotic supplementation in the prevention of common winter diseases in children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study.” Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease. Vol. 4, No. 5 (2010): 271–278.

- Gleeson, M., et al. “Daily probiotic’s (Lactobacillus casei Shirota) reduction of infection incidence in athletes.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. Vol. 21, No. 1 (2011): 55–64.

- Ahanchian, H., et al. “A multi-strain synbiotic may reduce viral respiratory infections in asthmatic children: A randomized controlled trial.” Electronic Physician. Vol. 8, No. 9 (2016): 2833–2839.

- Wang, Y., et al. “Probiotics for prevention and treatment of respiratory tract infections in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Medicine. Vol. 95, No. 31 (2016): e4509.

- Hempel, S., et al. “Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA. Vol. 307, No. 18 (2012): 1959–1969.

- Allen, S.J., et al. “Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Vol. 11 (2010): CD003048.

- McFarland, L.V., et al. “Systematic review and meta-analysis: Multi-strain probiotics as adjunct therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication and prevention of adverse events.” United European Gastroenterology Journal. Vol. 4, No. 4 (2016): 546–561.

- Bodean, O., et al. “Probiotics—A helpful additional therapy for bacterial vaginosis.” Journal of Medicine and Life. Vol. 6, No. 4 (2013): 434–436.

- Hanson, L., et al. “Probiotics for treatment and prevention of urogenital infections in women: A systematic review.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. Vol. 61, No. 3 (2016): 339–355.

- Sang, L.X., et al. “Remission induction and maintenance effect of probiotics on ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis.” World Journal of Gastroenterology. Vol. 16, No. 15 (2010): 1908–1915.

- Fujimori, S., et al. “High dose probiotic and prebiotic cotherapy for remission induction of active Crohn’s disease.” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Vol. 22, No. 8 (2007): 1199–1204.

- Sood, A., et al. “The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Vol. 7, No. 11 (2009): 1202–1209, 1209.e1.

- Tursi, A., et al. “Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.” The American Journal of Gastroenterology. Vol. 105, No. 10 (2010): 2218–2227.

- Zocco, M.A., et al. “Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis.” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Vol. 23, No. 11 (2006): 1567–1574.

- Steed, H., et al. “Clinical trial: The microbiological and immunological effects of synbiotic consumption—A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in active Crohn’s disease.” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Vol. 32, No. 7 (2010): 872–883.

- Zamani, B., et al. “Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic supplementation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.” International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. Vol. 19, No. 9 (2016): 869–879.

- Alipour, B., et al. “Effects of Lactobacillus casei supplementation on disease activity and inflammatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A randomized double-blind clinical trial.” International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. Vol. 17, No. 5 (2014): 519–527.

- Miraglia Del Giudice, M., et al. “Airways allergic inflammation and L. reuterii treatment in asthmatic children.” Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. Vol. 26, No. 1 Suppl. (2012): S35–S40.

- Chen, Y.S., et al. “Randomized placebo-controlled trial of Lactobacillus on asthmatic children with allergic rhinitis.” Pediatric Pulmonology. Vol. 45, No. 11 (2010): 1111–1120.

- Zuccotti, G., et al; Italian Society of Neonatology. “Probiotics for prevention of atopic diseases in infants: Systematic review and meta-analysis.” Allergy. Vol. 70, No. 11 (2015): 1356–1371.

- Zhang, G.Q., et al. “Probiotics for prevention of atopy and food hypersensitivity in early childhood: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Medicine. Vol. 95, No. 8 (2016): e2562.

Stores

Stores